Have You Ever Wondered: Why the Different Bibles?

Did you know that Catholics use a slightly different Bible than other Christian denominations? Have you ever wondered why?

Why the Differences?

A brief recap Jewish history to get some context:

- Around 1280 BC, Moses led the Chosen people to the Promised Land

- King David reigned around 1000 BC

- In 721 BC the Northern Kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians

- In 586 BC the Southern Kingdom of Judah fell to the Babylonians

As each kingdom fell, the Jews were exiled and scattered–or dispersed (“diaspora“)–around the region. In the Diaspora following the fall of the Southern Kingdom, many Jews settled in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, which was immersed in Greek language and culture. After about fifty years, the Persian Ruler, Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem, but a whole generation had been born and raised while living in foreign lands, many of whom chose to stay. As time passed and more Diaspora Jews spoke Greek, there was a desire to have a copy of the Jewish Sacred Scriptures translated into the Greek language.

Legend has it that 72 scholars set out to translate the Scriptures from Hebrew to Greek. The Greek word for seventy is “septuaginta,” which is why this translation is known as the Septuagint [sep-tue-ah-jint]. It was completed around 100 BC and was widely used by Jews outside of Jerusalem.

So then the New Testament came to be:

- The life, ministry, parables, teachings, miracles, crucifixion, and Resurrection of Jesus happened around 30-33AD.

- The Letters of Paul, Peter, James, John, and Jude were written to various Christian communities in the years that followed the Resurrection.

- These Letters were so profoundly powerful that they got passed around from community to community while the stories of Jesus were told and retold orally.

- Eventually the Gospels were written down and passed around as well.

- Since most people spoke and wrote in Greek, the Gospels and Letters were also composed in Greek.

Although the New Testament itself was written in Greek, since Jesus and the Apostles lived and traveled in and around Jerusalem and Judea, they probably did not use the Septuagint when they read from scrolls. They probably used scrolls written in Hebrew and Aramaic. Which brings us to the next part of the story…

When the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 AD, the Jews were once again in Diaspora. The collection of Scripture that these rabbis used became the official Jewish Bible, or what Jews call the Tanakh.

- Torah – the Law

- Nevi’im – Prophets

- Ketuvim – Wisdom

Taken together, it forms the acronym: TaNaKh

So now we have two different sources for what we know as the Old Testament – the Greek Septuagint (compiled around 100 BC) and the Hebrew Palestinian Canon (compiled around 70 AD).

Although Jesus and the apostles probably used the Hebrew scrolls (not the Septuagint), the early Greek-speaking Church definitely would have used the Greek Septuagint.

Fast forward to 382 AD, when St. Jerome was commissioned by the pope to officially translate the Old and New Testaments into Latin. St. Jerome crossed referenced many different versions, copies, fragments, and translations of the original text. Especially since the early Church had used the Greek Septuagint for over three centuries, the decision was made to used continue using that version (with the extra books) in his translation. St. Jerome’s Latin Bible became the “version commonly used,” or Vulgata in Latin, Vulgate in Greek. (Biblical scholars today refer to this as the Vulgate.)

During the Protestant Reformation (1500’s), Martin Luther translated the Bible into the vernacular, or the common language of the people (which was, in his case, German). When Luther offered his translation, he used the Palestinian Canon. Why? Scholars suggest a few different theories:

- The prevailing thought at the time was that this canon–with less books than the Septuagint–was older and therefore more authentic. While the books in the Palestinian canon are older (nothing past 500 BC), technically the Septuagint itself is older.

- The Jewish Tanakh does not use these additional books, so neither did Luther’s translation.

- Luther was also motivated to choose the Palestinian Canon because he was able to exclude books that didn’t agree with his theology, such as the teaching on purgatory (which finds its roots in 2 Maccabees 12:39-46).

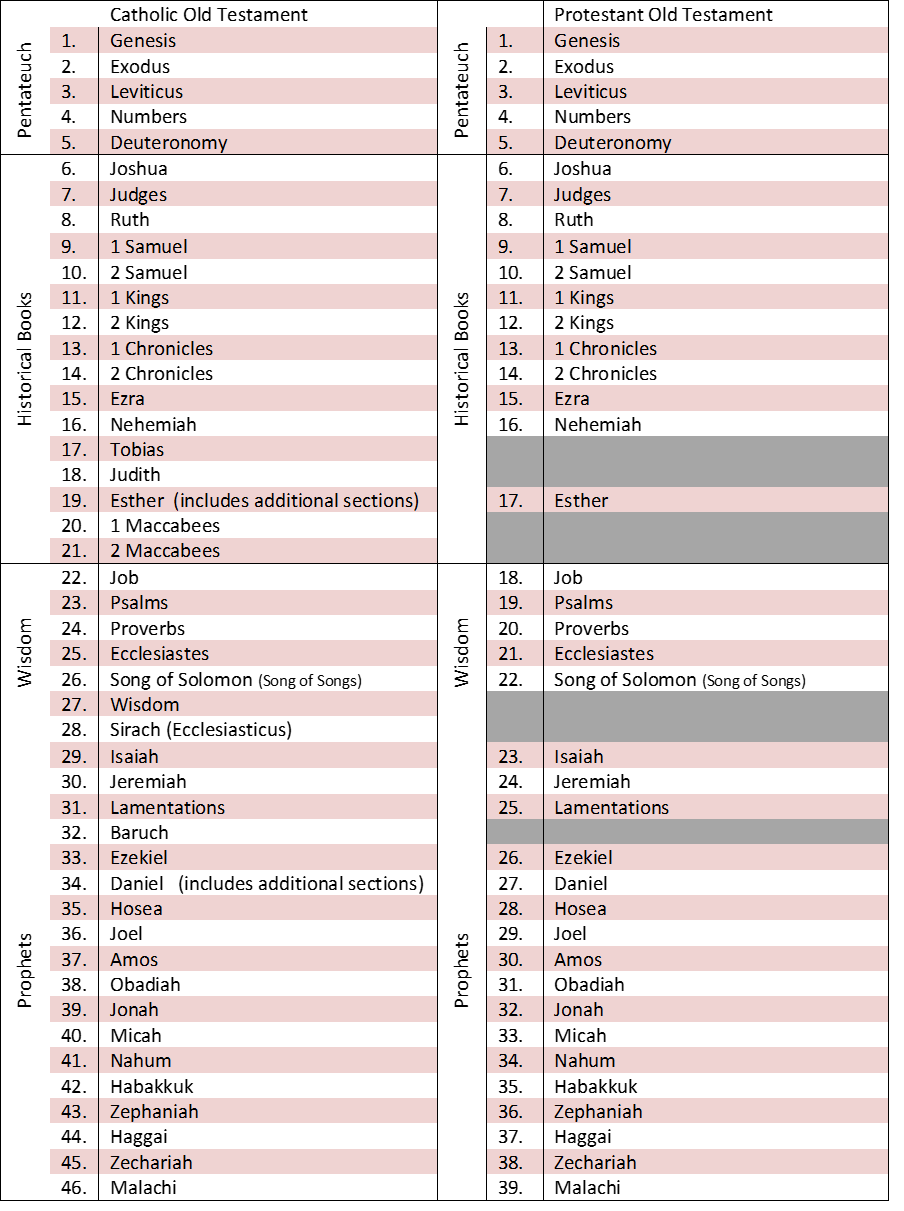

What are the Differences?

The Septuagint included seven whole books that are missing from the Palestinian Canon: Tobit, Judith, First Maccabees, Second Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach (sometimes called Ecclesiaticus), and Baruch, as well as a few sections of two other books: Esther and Daniel. Catholics refer to these (seven plus two) as deuterocanonical, meaning second canon. Protestants refer to them as apocryphial, meaning “hidden.”