Morality Part 4: Form, Inform, and Follow

When I do laundry, after washing and drying, I’ll transport the clean clothes to the couch. The couch and coffee table are my folding zone, a task I’ll tackle while watching Netflix, talking on the phone, or visiting with a close friend (one whom I am secure enough to expose my family’s laundry to). The reality is that the folding does not happen immediately. Often the couch is buried amid several loads of clean laundry. Yes, I’ll get to it. Eventually. The thing is that my kids will want to actually use the couch to sit on, despite the piles of clean laundry. Sometimes I take a little too long to get around to folding; I take responsibility for this.

Other times, like today, I’m within the margin of acceptable laundry-folding time. Regardless, the clean laundry got knocked off the couch by one of my kids.

Max: I fink I did it. I’m sowwy, Mommy. I didn’t mean to.

I know that he didn’t intentionally, maliciously knock my laundry on the floor, but still. He could’ve been more careful. And even if it was an accident, he could’ve fixed it.

While laundry on the couch isn’t one of the most pressing moral issues of our time, this conversation with my 6 year-old does provide a framework for examining moral responsibility.

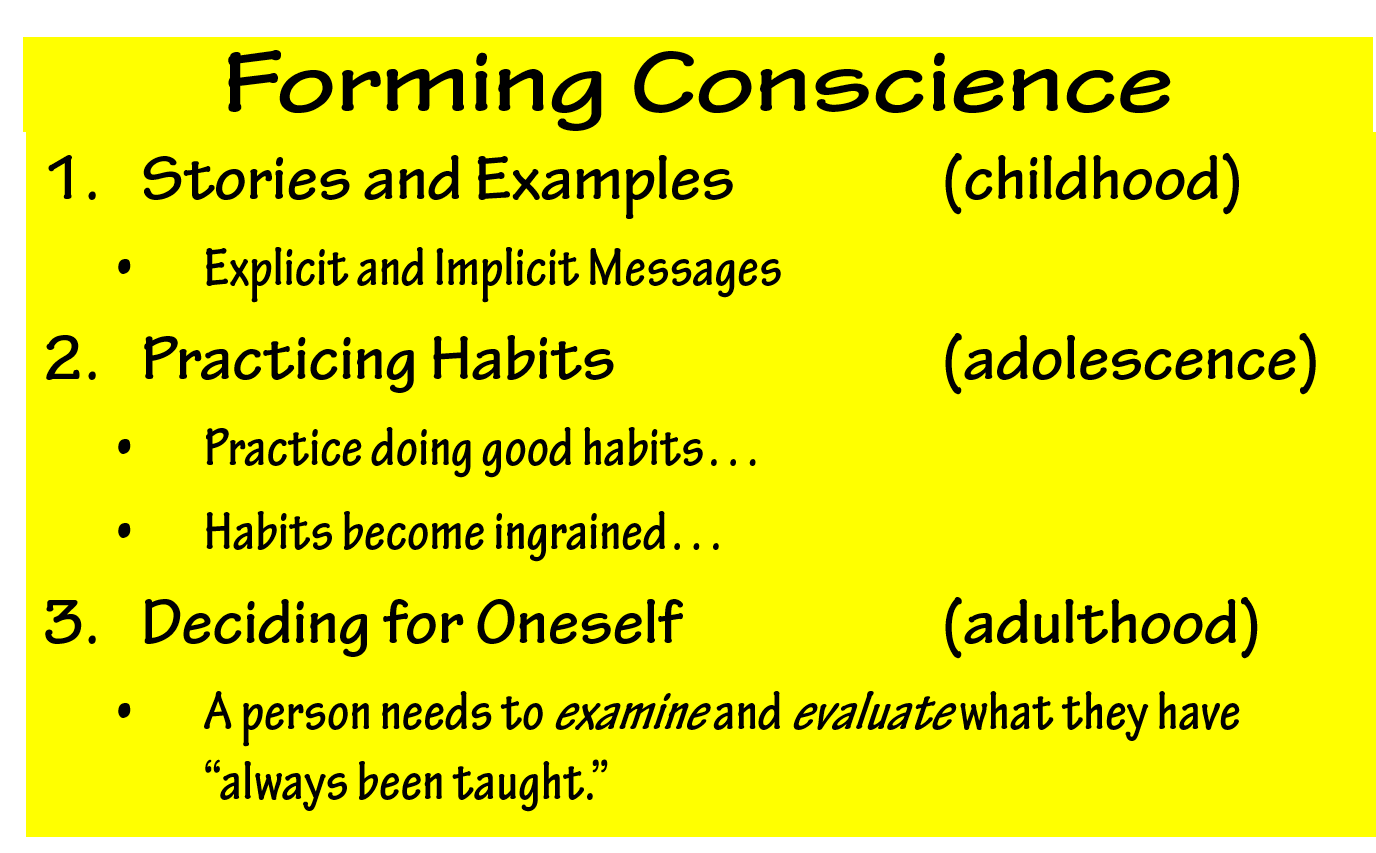

First, let’s recall where we left off: Morality Part 3 explained the lifelong process of forming conscience.

In my explanation of forming conscience, I gave a lot of attention to the idea that a person must genuinely choose what is good. However, saying a person must decide to do what is good for oneself is not the same thing as saying that a person makes moral decisions by oneself.

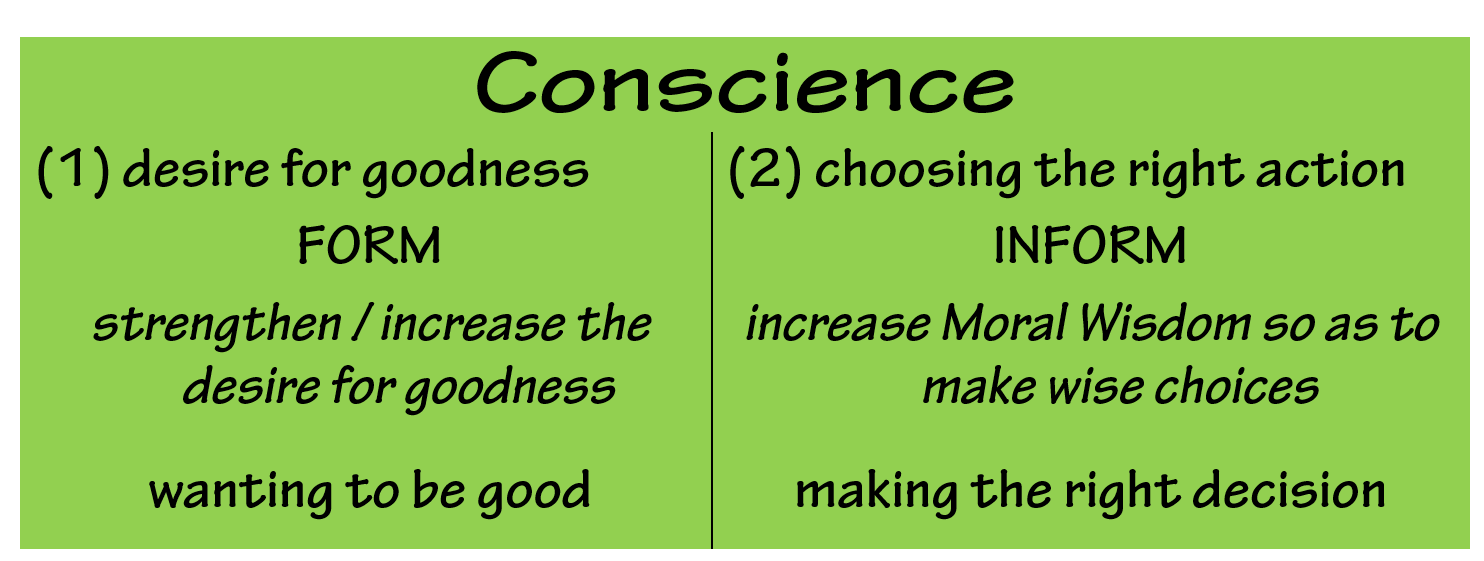

This is where Informing Conscience comes in. If forming conscience is about wanting to be a good (not bad) person, having an informed conscience is about making right (not wrong) choices. Quite simply, it’s about making informed decisions.

How do we make informed moral decisions? The Catechism explains that we do this by consulting with three areas of our life: self, others, and God.

1. Self – (“assisted by the virtue of prudence“) Quite simply: stop and think. Mindful self-examination helps in discernment, whether or not we actually write out that pro and con list. Here, we take the time to differentiate between wants and needs… between immediate gratification and long-term impact…

2. Others – (“assisted by…the advice of competent people“) Inviting the wisdom of others is not the same thing as allowing “superego” to decide for us. In fact, think of this as your own Personal Board of Directors. While unsolicited advice will be offered far and wide, you find yourself talking through difficult decisions with a select group of people. Each member of this board is must be personally appointed by you as a closest, trusted adviser; no applications (or self-nominations) are accepted. It’s not that the people on your Board tell you what to do (because you may not always follow their advice), but you do seriously consider whatever they have to say.

That said, it is important that we neither appoint strictly “yes-men” nor superegos that micro-manage our decisions. Our Personal Board of Directors should give us insight into our darker selves, but do so with selfless agape-love.

Alongside your Personal Board of Directors, the independent research of a respected third party should be considered when making difficult decisions. The voice of “competent people” extends to the sciences, particularly the social sciences.

3. God – (“the help of the Holy Spirit“) In making moral decisions, we must pray–inviting God into the discernment process. Additionally, part of being Catholic means that we value the 2000+ years of wisdom from Scripture and Tradition, which is one of the big ways that the Holy Spirit speaks to us today.

There is a temptation to approach the teachings of the Church and the role of the Magisterium as the voice of superego. For some of us, that means we blindly follow an unexamined faith. For others, it means we ignore the voice of the Holy Spirit. Neither of these approaches reflects having a truly informed conscience.

What we don’t want to do is end up uninviting the Holy Spirit from our Personal Board of Directors. The key is to earnestly listen to the wisdom of the teachings of the Church. If we find ourselves in disagreement with the Church, we owe it to our faith to explore this disconnect. Sometimes it’s a matter of understanding why the Church teaches what it does. It’s not ok for a person to simply dismiss a teaching that they don’t agree with; rather, this is a reason for deeper prayer, study, and exploration in faith.

- What is your decision making process? In what way does it align with the self-others-God explanation of CCC, 1788? In what way does it differ?

- Who is on your Personal Board of Directors? Have you appointed any “yes-men” or superegos?

- What insights do you gain from thinking about informing conscience in this way?

Follow Your Conscience

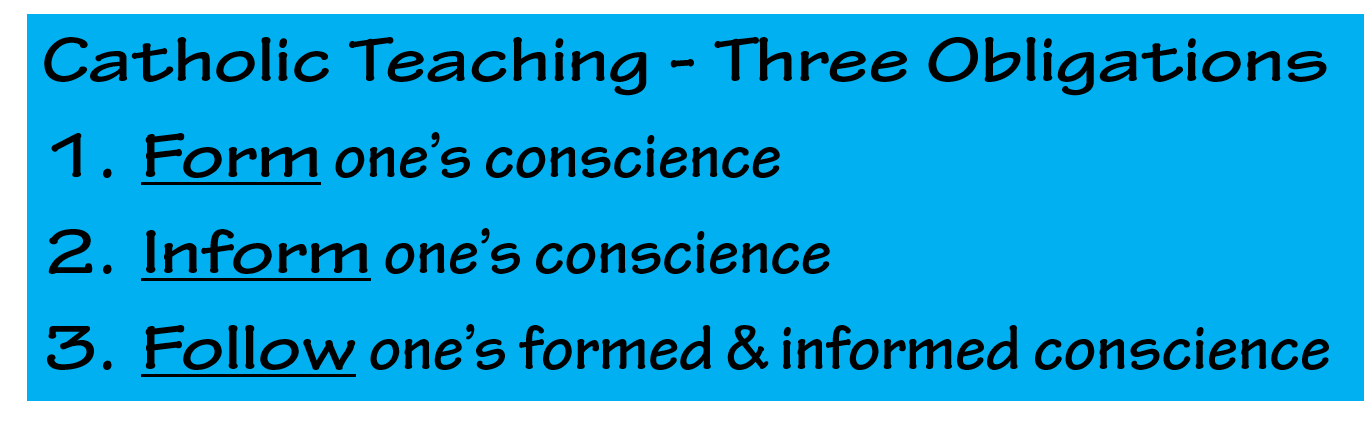

Catholic Teaching insists that we have an obligation to follow our conscience, but stated more precisely, we have an obligation to follow our formed and informed conscience.

It is in this context that it makes sense to return to a discussion about moral responsibility and sin, because it is our conscience that enables us to take responsibility for our actions (CCC, 1781).

How can we say something is “wrong” if you’re following your conscience?

Faced with a moral choice, our conscience can either make a right judgment or a wrong one. Sometimes, we will be following our conscience and still end up making a mistake, which Catholic tradition calls “erroneous conscience” (CCC, 1786, 1790). Actually, there are different levels of assessment here:

- Invincible Ignorance – if a person honestly did not know something was wrong (and there is not a reasonable expectation that they should have known), then it is considered a true accident.

- Although the person may have done something wrong, they are not in violation of their conscience.

- It is expected that they will make amends for any damage done, but they are not morally responsible. (See CCC, 1793)

- Vincible Ignorance – if a person claims that they didn’t know something was wrong, but when we logically assess the situation, we can safely say that they should have known better. In the court of law, we call this negligence.

- When a wrongdoing falls under this umbrella of “willful ignorance,” the person bears moral responsibility, but it is still not considered a “sin” (CCC, 1791-1792).

- Sin – For something to be considered a sin, it must be a deliberate decision to violate our conscience. Therein, we must have both:

- Knowledge that it is wrong

- Freedom to choose

There are times when we know what is wrong, but we do it anyway. St. Augustine tells a story from his adolescence (in Book 2, Chapter IV of his Confessions) when he stole some pears. He knew it was wrong; he admits that he was neither hungry, nor poor when he did it. He stole them for the thrill of stealing – simply because it was forbidden.

We all have a pear-tree story of our own; a time which we were clearly choosing to do something that was in violation of our conscience.

The next post on Morality will explore and unpack some of the traditional vocabulary surrounding sin. For now, consider the following:

- Can you relate to these three categories of “doing something wrong” – invincible ignorance (accident), vincible ignorance (negligence), and sin (deliberate decision)? Which do you struggle with most and why?

“Pears Growing on Pear Tree © Depositphotos.com/Digifuture”